Down’s Syndrome

Occurs in approximately 1 out of every 800 babies born alive, and it is caused by a genetic abnormality that affects something called a chromosome.

Chromosomes are like tiny instruction manuals inside our cells. They’re made of DNA, which contains all the information our bodies need to grow, develop, and function.

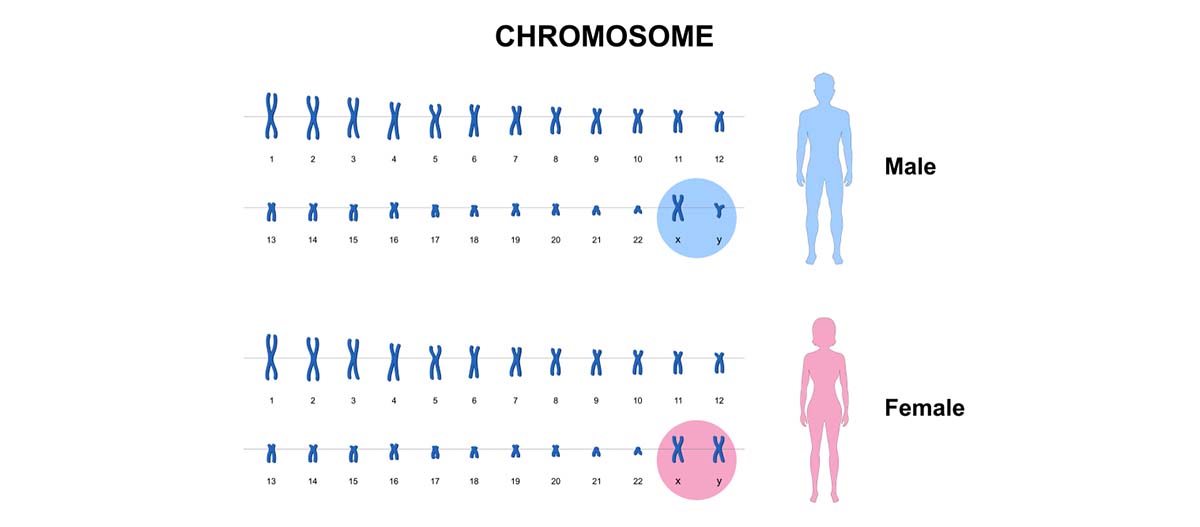

Most humans have 46 chromosomes, which come in pairs. One set of chromosomes comes from each parent. These pairs include 22 pairs of “autosomal” chromosomes and one pair of “sex” chromosomes. The sex chromosomes determine if we’re male (XY) or female (XX).

Each chromosome carries many genes, which are like individual pages in the instruction manual. Genes tell our bodies how to make proteins, which are the building blocks for everything we need, like hair, skin, and organs.

During cell division, chromosomes make sure each new cell gets a complete set of instructions. Any mistakes or changes in chromosomes can cause genetic conditions or health problems.

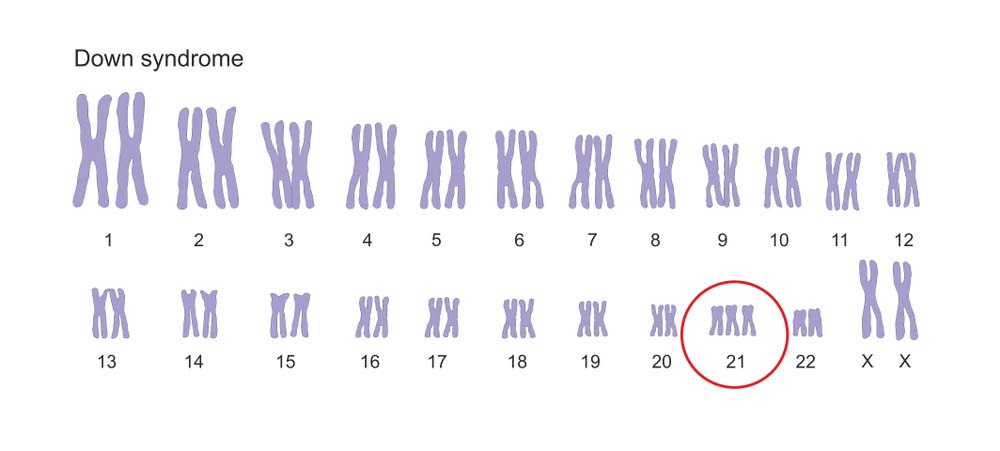

People with Down’s syndrome are born with three, rather than two, copies of chromosome 21. Scientists do not know why some babies wind up with the extra chromosome, but they do know that the age of the mother plays a role. As a female gets older, the risk of having a baby with Down’s syndrome steadily increases.

This additional genetic material alters the course of development, resulting in distinct physical characteristics, intellectual differences, and potential medical issues. While every individual with Down syndrome is unique, some common traits include:

- Facial features: Characteristic facial appearance, including a flattened nasal bridge, slanted almond-shaped eyes, protruding tongue and unusual-looking ears.

- A crease across the palm, called a transverse palmar crease or a Simian crease

- A wide gap between the first and second toes (sandal gap deformity)

- Intellectual disability: Individuals with Down’s syndrome typically have mild to moderate intellectual impairment, but each person’s abilities and strengths vary widely. Despite the disability, most children with Down’s syndrome can learn basic tasks; they just take a little longer than other babies to do so. For example a typically developing child will usually sit at about 6 months and walk at 13 months, but a child with Ds may on average do so at 11 months and 2 years respectively. Speech with first spoken words will be delayed at about 18 months+.

- Medical conditions: Certain health issues are more prevalent among individuals with Down’s syndrome, such as congenital heart defects (about half of babies with Ds), gastrointestinal abnormalities such as coeliac disease and thyroid disorders where the body doesn’t make enough thyroid hormone. They are more prone to ear infections and hearing loss, and visual impairments which are usually correctible with glasses. Sleep apnoea is very common in children with Down’s syndrome. Blood abnormalities including cancer of the blood like leukemia are more frequent in Ds.

- People with Down’s syndrome often have too much flexibility between the bones at the top of the spine that support the head (called atlantoaxial instability). Often, this condition causes no symptoms, but it can compress the spine, cause pain, or cause the head to tilt to one side. In extreme cases, this joint instability can cause paralysis. Children who participate in sports should have a physical examination to look for signs of joint instability.

Some of these complications are more serious than others, but most of them can be treated. To make sure that complications are appropriately managed as they emerge, a child with Ds should be screened at frequent intervals.

Screening for Down’s syndrome

This is typically offered to pregnant individuals to assess the likelihood of their baby having the condition. There are primarily two types of screening tests available:

- First-Trimester Screening: This involves a combination of ultrasound and blood tests performed between 11 and 14 weeks of pregnancy. The ultrasound, called a nuchal translucency (NT) scan, measures the thickness of the fluid at the back of the baby’s neck. A blood test measures levels of certain proteins and hormones in the mother’s blood. The results of these tests, along with the mother’s age and other factors, are used to estimate the risk of the baby having Down’s syndrome.

- Second-Trimester Screening: Also known as the quad screen or multiple marker screening, this test is typically performed between 15 and 20 weeks of pregnancy. It involves a blood test that measures the levels of certain proteins and hormones in the mother’s blood. These levels, along with factors such as the mother’s age and ethnicity, are used to estimate the risk of the baby having Down’s syndrome.

It’s important to note that screening tests do not provide a definitive diagnosis of Down’s syndrome but rather estimate the likelihood of the condition. If the screening results indicate an increased risk, further diagnostic testing, such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis, may be recommended to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Screening and diagnostic tests for Down’s syndrome are voluntary. It’s essential for pregnant women to discuss their options and preferences regarding Down’s syndrome screening with their healthcare provider to make informed decisions about their care.

Treatment

There is no treatment specifically for Down’s syndrome, but there are several important treatments for the complications of the condition. That is why it is important to have children screened for these complications at regular intervals throughout their youth.

Medical Management and Early Intervention:

Early intervention is key to optimizing outcomes for children with Down syndrome. As paediatricians, we play a crucial role in providing comprehensive medical care and facilitating access to early intervention services. Some essential aspects of medical management include:

- Regular health check-ups: Routine medical evaluations to monitor growth, development, and overall health, including screenings for associated medical conditions.

- Developmental assessments: Ongoing evaluations to track developmental milestones and identify areas where interventions may be beneficial.

- Therapies and interventions: Access to therapies such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and behavioral interventions to address specific needs and promote skill development.

- Family support: Providing guidance, resources, and emotional support to families as they navigate the challenges and joys of raising a child with Down’s syndrome.

Having children routinely screened can help ensure that they will get the appropriate treatment as soon as any Down syndrome-related complications arise. That can be important for serious complications as well as for not-so-serious ones. For example, children may need corrective surgery to treat a heart defect. Or, children may need eyeglasses or hearing aids, not only to improve vision or hearing, but also to maximize their ability to learn and understand.

Down’s Syndrome Prognosis

The prognosis for a child with Down syndrome used to be pretty grim. In 1983, the average lifespan of a person with the condition was just 25 years. Thanks to advances in the treatment and screening of people with Down syndrome, the average lifespan is approximately 60 years.

As medicine continues to evolve, the outlook for people with Down syndrome will probably keep improving. Even now, many children with the condition go on to have full and happy lives, so long as they have the right support.

Where to get more information and support:

https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/downsyndrome