Febrile Seizures

Febrile seizure is a fit that can happen when a child has a fever (temperature of 38 degrees Celcius or above). They are relatively common and, in most cases, aren’t serious.

Around one in 20 children will have at least one febrile seizure at some point. They most often occur between the ages of six months and 6 years.

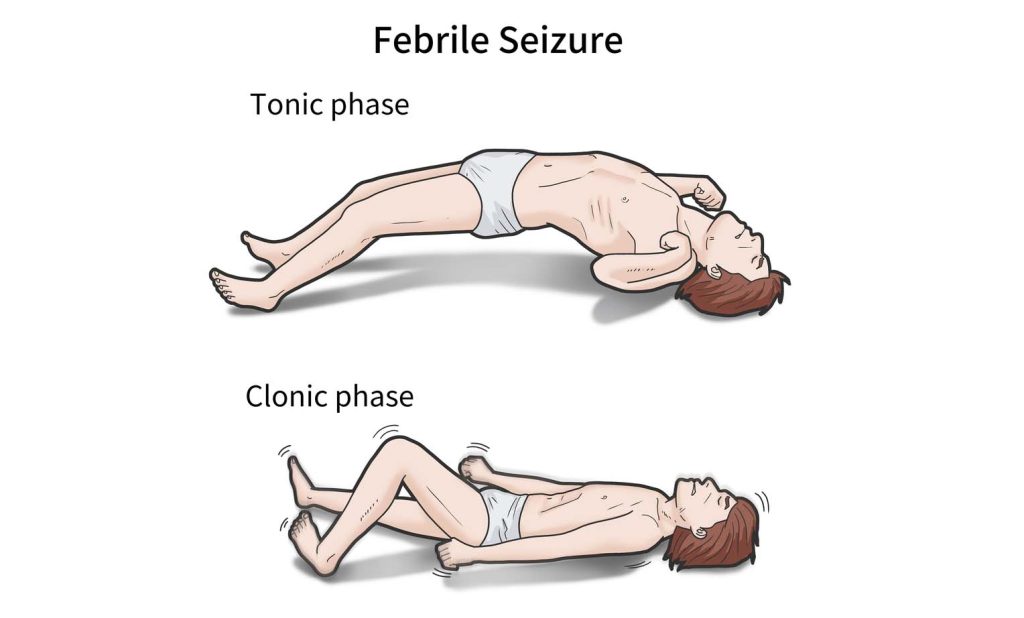

During a febrile seizure, the child’s body usually becomes stiff, they lose consciousness and their arms and legs twitch. Some children may wet or soil themselves. Following the seizure, they may be sleepy for up to an hour.

What to do during a seizure?

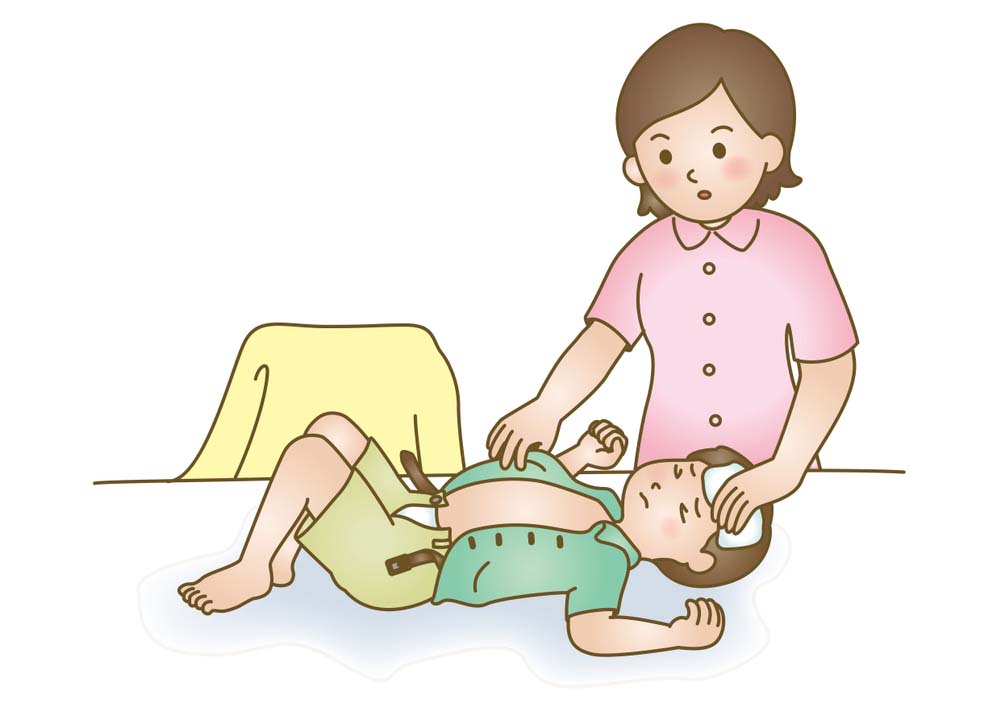

If your child is having a febrile seizure, place them in the recovery position. Lay them on their side, with the head placed on a soft surface, with their face turned to one side. This will stop them swallowing any vomit, keep their airway open and help prevent injury.

Stay with your child and try to make a note of how long the seizure lasts.

If it’s your child’s first seizure, or it lasts longer than five minutes, take them to the nearest hospital, as soon as possible. While it’s unlikely that there’s anything seriously wrong, it’s best to be sure.

If your child has had febrile seizures before and the seizure lasts for less than five minutes, phone your doctor or go to the nearest hospital.

Don’t put anything, including medication, in your child’s mouth during a seizure because there’s a slight chance that they might bite their tongue.

Almost all children make a complete recovery after having a febrile seizure.

Types of febrile seizure

There are two main types of febrile seizure.

Simple febrile seizure

A simple febrile seizure is the most common type of febrile seizure, accounting for about eight out of 10 cases. It’s a fit that:

-

- Is generalized– involving stiffening and twitching of the whole body

- lasts less than 15 minutes

- doesn’t reoccur within 24 hours or the period in which your child has an illness

- has a recovery period under 1 hour

Complex febrile seizure

Complex febrile seizures are less common, accounting for two out of 10 cases. A complex febrile seizure is any seizure that has one or more of the following features:

-

- the seizure lasts longer than 15 minutes

- your child only has symptoms in one part of their body (this is known as a partial or focal seizure)

- your child has another seizure within 24 hours of the first seizure, or during the same period of illness

- your child doesn’t fully recover from the seizure within one hour

Why febrile seizures occur

The cause of febrile seizures is unknown, although they’re linked to the start of a fever (a high temperature of 38C). In most cases, a high temperature is caused by an infection such as:

- viral infections like chicken pox, influenza, roseola

- bacterial infections like tonsillitis, ear infection, gastroenteritis (tummy bug)

There may also be a genetic link to febrile seizures because the chances of having a seizure are increased if a close family member has a history of them. Around one in four children affected by febrile seizures has a family history of the condition. If a child has a first-degree relative (mother, father, sister or brother) with a history of febrile seizures, their risk of having seizures increases. The more relatives affected, the higher the risk.

Vaccinations

In rare cases, febrile seizures can occur after a child has a vaccination. Research has shown that your child has a one in 3,000 to 4,000 chance of having a febrile seizure after having the MMR vaccine.

Febrile seizures and epilepsy

Many parents worry that if their child has one or more febrile seizures, they’ll develop epilepsy when they get older. Epilepsy is a condition where a person has repeated seizures without fever.

While it’s true that children who have a history of febrile seizures have an increased risk of developing epilepsy, it should be stressed that the risk is still small.

It’s estimated that children with a history of simple febrile seizures have a one in 50 chance of developing epilepsy in later life. Children with a history of complex febrile seizures have a one in 20 chance of developing epilepsy in later life.

This is compared to around a one in 100 chance for people who haven’t had febrile seizures.

Diagnosing febrile seizures

Febrile seizures can often be diagnosed from a description of what happened.

Further tests may be needed if the cause of the associated infection isn’t clear. A blood or urine sample may be needed to test for signs of infection.

It’s unlikely that your doctor will see the seizure, so an account of what happened is useful.

It’s useful to know:

- how long the seizure lasted

- what happened – body stiffening, twitching of the face, arms and legs, staring and loss of consciousness

- whether your child recovered within one hour

- whether they’ve had a seizure before

Sometimes a test may be necessary to rule out rarer conditions which can cause similar symptoms, such as meningitis.

Further tests

Further tests may be carried out in hospital if your child’s symptoms are unusual – for example, if they don’t have a high temperature or their seizures don’t follow the normal pattern.

Further testing and observation in hospital is also usually recommended if your child is having complex febrile seizures, including an electroencephalogram and lumbar puncture, particularly if they’re less than 12 months old.

Electroencephalogram

An electroencephalogram (EEG) measures your child’s electrical brain activity through electrodes that are placed on their scalp. Unusual patterns of brain activity can sometimes indicate epilepsy.

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture can be used to determine whether your child has an infection of the brain or nervous system (Meningitis). During this test a hollow needle is inserted into the base of the spine to obtain a small sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is a clear fluid that surrounds and protects the brain and spinal cord. A local anaesthetic will be used to numb your child’s back so that they don’t feel any pain.

Treating febrile seizures

In many cases, febrile seizures do not need to be treated, although care should be taken to deal with a seizure as it happens.

High temperature (fever)

Reducing a high temperature can help make your child feel more comfortable. Anti-fever medication like paracetamol and ibuprofen have been shown to be effective in reducing a high temperature. However, they won’t reduce the chances of your child actually having a seizure.

Removing any unnecessary clothes and bedding will also help to lower your child’s temperature.

Aspirin should never be given to children under 16 years of age because there’s a small risk that the medication could trigger a condition called Reye’s syndrome, which can cause brain and liver damage.

The use of cold sponges or fans isn’t recommended for treating a high temperature. There’s little evidence that they’re effective, and they may cause your child discomfort. It’s also important to prevent dehydration during a fever by making sure your child drinks plenty of fluids.

Recurring febrile seizures

About one third of children will have a febrile seizure again during a subsequent infection. This often occurs within a year of the first febrile seizure.

Recurrence is more likely if:

- the first febrile seizure occurred before your child was 18 months old

- there’s a history of seizures or epilepsy in your family

- before having the first seizure your child had a fever that lasted less than one hour or their temperature was less than 40C.

- your child has complex febrile seizures.

- your child attends a day care or nursery (this increases their chances of developing common childhood infections).

It’s not recommended that your child is given a prescription of regular medicines to prevent further febrile seizures. This is because the adverse side effects associated with many medicines outweigh any risks of the seizures themselves.

Research has shown that the use of medication to control fever isn’t likely to prevent recurrence of further febrile seizures.

However, there may be exceptional circumstances where medication to prevent recurrent febrile seizures is recommended. For example, children may need medication if they have a low threshold for having seizures during illness, particularly if the seizures are prolonged. In this case, your child may be prescribed certain anti-seizure medicines.

Children who’ve had a febrile seizure following a routine vaccination (which is very rare), are no more at risk of having another seizure compared to children who’ve had a seizure due to another cause for fever.